Balor et Yspaddaden Penkawr de par le monde

A propos du motif F571.1

Patrice Lajoye

MRSH - Université de Caen Basse-Normandie

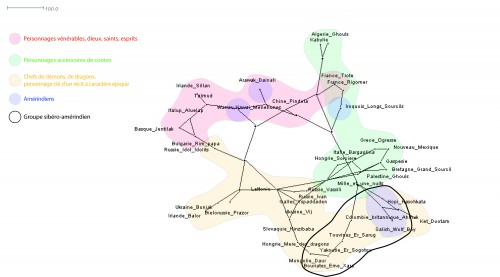

Abstract: The Irish Balor and the Welsh Yspaddaden Penkawr are creatures most often regarded as belonging only to the Celtic mythology. But there are quite similar creatures in many places in Eurasia and the Americas. This article presents the corpus and seeks to determine the origins, or at least the history of this character, using a combination of classical philological analysis, semiotics, and use of statistical tools used in phylogenetics.

Keywords: Balor, Yspaddaden, Vij, F571.1 Motif, History of myths.

Résumé: L'Irlandais Balor et le Gallois Yspaddaden Penkawr sont des créatures le plus souvent considérées comme relevant uniquement de la mythologie celtique. Mais il existe en de nombreux endroits d'Eurasie et des Amériques des créatures tout à fait similaires. Cet article en présente le corpus et s'efforce de déterminer les origines, ou du moins d'histoire de ce personnage, en utilisant une combinaison d'analyse philologique classique, de sémiotique, et d'utilisation des outils statistiques employés en phylogénétique.

Mots clés : Balor, Yspaddaden, Vij, Motif F571.1, histoire des mythes.

Télécharger l'article en pdf / download in pdf: Lajoye2.pdf

Cité par / quoted by:

Martin Bless, « Could a primeval version of the Basque 'Jentilak' tale be 25.000-year-old? »,Journal of Brief Ideas, 2016,http://beta.briefideas.org/ideas/e5de088102b2752e8ff7b0f97af43f9d

Julien d'Huy and Yuri Berezkin, « How Did the First Humans Perceive the Starry Night? On the Pleiades », The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter, 12-13, 2017, p. 100-122.

Edward Pettit, « The bristle of Balar’s boar, Diarmaid’s misstep and the gae bolga: background and analogues », Studia Hibernica, 44, 2018, p. 35-78.

Lorsqu'en 2012 je proposais aux celtisants tout une série de comparaisons mythologiques entre Celtes et Slaves, j'abordais le cas des créatures démoniaques irlandaises et galloises bien connues que sont Balor et Yspaddaden Penkawr, tout en leur donnant des corrélats précis et abondants, non seulement chez les Slaves, mais aussi en Amérique du Nord. Il était question alors d'une créature, souvent âgée, dotée de sourcils ou de paupières très longs au point de lui masquer la vue, et à qui un intervenant extérieur est nécessaire pour soulever ces sourcils ou paupières. Il s'agit du motif F571.1, Old man with hanging eyelids (qu'on associera avec F441.4.5. Wood-spirits with such heavy eyebrows they must lie on backs to see upwards), avec toutefois une définition bien plus précise que celle proposée par Stith Thompson, qui se contentait d'un : « Old man with hanging eyelids. So old that the eyelids hang down to his chin and must be lifted up ». J'ignorais cependant alors certaines choses. Tout d'abord que ces parallèles celto-slaves avait déjà été esquissés, même si très brièvement, dès le XIXe siècle. En 1892, le folkloriste russe Nikolaï Soumtsov, prenant pour base Vij, personnage de fiction de Nicolas Gogol, en vint à dire : « le conte sur Balor rappelle le Vij de Gogol ». Bien plus tard, et de façon tout à fait indépendante, Alexandre Haggerty Krappe proposa lui aussi un rapprochement entre Yspaddaden et Vij, ainsi qu'avec Les Merveilles de Rigomer, un roman arthurien méconnu, et avec un personnage de conte slovaque. Mais il le fit cependant sur la base d'informations données par W. R. S. Ralston, incomplètes, voire fausses, ce qui le conduisit à faire de Vij... un personnage serbe. Ce même auteur s'engageait cependant dans une comparaison infructueuse entre Balor et le grec Argos, ce qui fit que sa note ne fut jamais reprise, sauf brièvement, en 1997, par Christine Goldberg, en marge d'une étude sur le conte-type AT 408, « les trois oranges », mais sans approfondissements. De fait, en 1971 puis en 1973, le russe Viatcheslav Ivanov est resté bien isolé en relevant les parallèles importants qui pouvaient exister entre les personnages celtiques, la nouvelle de Gogol et un conte russe d'Afanassiev.

Depuis, nos deux personnages sont restés sans comparaisons possible, et donc a priori uniquement celtiques. Jusqu'à ce que je produise mon article de 2012, relevant les comparaisons slaves. Mais il s'avère cependant que l'on trouve un peu partout en Europe et dans ses marges des personnages de contes très similaires, voire totalement identiques. J'en proposerai ici une ébauche de corpus puis une tentative d'analyse.

Ière partie

Un essai d'inventaire

Domaine celtique

Balor

Balor est donc un des trois rois des Fomore, les démons irlandais, sans doute le plus puissant, de par le pouvoir de son œil. Il apparaît déjà dans le Livre des Conquêtes de l'Irlande (XIIe siècle), mais est surtout présent dans les deux versions de la Seconde bataille de Mag Tured. Il est le grand-père du Lug, champion des dieux. Lorsque le combat doit commencer, Nuada, jaloux, fait emprisonner Lug et l'enchaîne. Lug, endormi, est réveillé par le bruit des combats. Il arrache alors ses chaînes et se précipite avec elles et les pierres qui le retenaient sur le champ de bataille. Là, les Fomore prennent peur face à sa colère : le combat s'arrête momentanément. Il ne reprendra que lorsque Lug sera officiellement chef de l'armée des dieux. Alors, les Fomore lancent Balor dans la bataille.

« Lug et Balor à l'oeil perçant se rencontrèrent dans la bataille. Balor avait un œil maléfique qui n'était jamais ouvert, excepté sur le champ de bataille. Quatre hommes en soulevaient la paupière avec un crochet [anneau] poli. Si une armée regardait cet œil, elle ne pouvait résister à quelques guerriers, quand bien même elle était au nombre de plusieurs milliers d'hommes. Il y avait du poison en lui : un jour que les druides de son père étaient en train de bouillir des charmes il vint et regarda par la fenêtre, si bien que la fumée de l'ébullition vint jusqu'à lui et que le poison lui entra dans l'oeil. Il rencontra alors Lug. Lug dit : 'Ô dieux (?), qui sont les hommes qui... ?...'

'Soulève ma paupière, ô garçon, dit Balor, pour que je voie le bavard qui me parle.'

On leva la paupière de l'oeil de Balor. Lug lui lança alors une pierre de fronde, si bien que l'oeil lui traversa la tête. Et c'était sa propre armée qui regardait. Balor tomba sur l'armée des Fomoire et trois fois neuf hommes en moururent à côté de lui. »

« Il fut proclamé par eux de dégager l'oeil empoissonné et venimeux, dangereux et destructeur de Balor, de ses chaînes et de ses liens. Se levèrent alors trois fois neuf bons guerriers pour libérer l'épaisse paroi et la peau parcheminée, et le voile neuf, épais et large. Les TDD saisirent alors l'abri de leurs épais boucliers et de leur ombre pour que le jet de flot de venin de l'oeil empoissonné ne les atteignît pas et ils se mirent le haut du corps, la poitrine et le visage à l'abri du bouclier, à l'exception du guerrier brave et tenace, le lion rapide et coléreux, Lugh au Long Bras, le héros aux grands coups, car il attendait lui-même résolument pour lancer ses pierres rondes de fronde. »

Peu après, Goibnionn, le forgeron des dieux, promet à Lug de lui envoyer une balle de fronde qui permet à celui-ci de vaincre. Alors Balor déclare :

« Fe fe fo fo aicthe aicthe, aille aille, soulevez-moi la fermeture de mon œil pour que je voie le guerrier bavard qui me parle. Qui es-tu, ô petit homme ? ... »

Et tandis que l'oeil de Balor s'ouvre, Goibnionn lance la balle de fronde, que Lugh renvoie directement dans la tête de son adversaire, retournant le regard du monstre contre ses propres servants.

Balor, s'il dispose d'un œil maléfique, n'est pour autant pas un cyclope. Le poison de son œil n'est pas mortel en soi, mais il a un effet paralysant sur les troupes adversaires, au point que seul Lug peut l'affronter, avec l'aide d'un forgeron. On remarquera aussi que ses paupières sont maintenues en place à l'aide de chaînes et de liens. La formule Fe fe fo fo aicthe aicthe, aille aille montre que le rédacteur tardif de la seconde version fait de lui une sorte d'ogre, tels ceux que l'on trouve dans les contes populaires en Irlande et bien au-delà. De fait, Balor, au XIXe siècle, était toujours connu par plusieurs versions d'un même récit oral racontant la conception et la naissance de Lug, versions dans lesquels il arrive que Lug tue Balor d'un coup de barre de fer dans l’œil.

Saint Sillan de Imleach Cassain

Ce saint méconnu, dit aussi Sillan de Imbliuch Cassain, était fêté le 11 septembre. Une scholie médiévale ajoutée au Martyrologe d'Oengus indique que ce saint possédait, dans ses sourcils, un poil empoisonné qui tuait rapidement la première personne qu'il voyait au lever du jour. Aussi beaucoup de malades venaient-ils lui rendre visite dans l'espoir d'abréger leurs souffrances. Cela dura jusqu'à ce que saint Molaisse n'arrache, au prix de sa vie, le poil en question.

Il n'est pas question ici d'un soulèvement artificiel de paupière ou de sourcil, mais il faut noter que le pouvoir du saint s'exerce au point du jour, lorsque Sillan ouvre la première fois les yeux. Il aura fallu que celui-ci soit en quelque sorte coiffé pour que cela cesse. Il faut noter que ce coiffage a sans doute entraîné la mort du saint. En effet, saint Molaisse est fêté le 12 septembre, date de sa mort, soit au lendemain de la fête de Sillan, laquelle, de ce fait, commémore sans doute la mort de celui-ci.

Yspaddaden Penkawr

Yspaddaden Penkawr est essentiellement connu par un récit gallois du Moyen Âge central, Kulhwch et Olwen. Il a cependant laissé quelques infimes traces dans la toponymie, ce qui laisse à penser qu'un folklore plus tardif a pu exister. Kulhwch est le fils d'un roi veuf, lequel s'étant remarié, eut pour seconde épouse une jeune femme jalouse qui maudit Kulhwch en l'obligeant à n'avoir pour femme que Olwen, la fille d'Yspaddaden Penkawr (« Chef des Géants »). Le héros obtient l'aide du roi Arthur, et ensemble, avec toute la cour, ils se rendent chez Yspaddaden. En chemin, ils rencontrent Custenhin, le berger d'Yspaddaden, un homme dont le chien est capable de tout brûler de son souffle comme un dragon, et sa femme, en fait la tante de Kulhwch. Tous deux leur font bon accueil et les aident à rencontrer Olwen. Mais l'accord du père est nécessaire au mariage, aussi se rendent-ils à son château :

« Ils se levèrent pour la suivre dans le château ; ils tuèrent neuf portiers gardant les neuf portes, sans qu'aucun n'ait pu crier, et ils tuèrent les neuf chiens de garde sans qu'aucun n'ait pu couiner. Ils marchèrent droit vers la grande salle.

'Salut à toi, Yspaddaden Chef des Géants, dirent-ils, au nom de Dieu et des hommes.

- Et vous, pourquoi venez-vous ici ?

- Nous venons demander ta fille Olwen pour Kulhwch fils de Kilydd.

- Où sont mes serviteurs, ces manants, ces gens de rien ? dit-il. Levez les fourches sous mes deux sourcils pour que je puisse voir mon futur gendre.'

Cela fut exécuté.

'Revenez demain, je vous donnerai une réponse. »

Et lorsque tout le monde sort, Yspaddaden saisit une lance qu'il projette vers eux, mais elle est rattrapée au vol par quelqu'un qui lui la réexpédie. La scène se répète trois fois, aussi le géant est-il touché aux genoux, puis à la poitrine, puis aux yeux. A la quatrième visite, le géant ne lance plus rien mais pose enfin ses exigences : il s'agit d'aller quérir les objets qui seront nécessaires au mariage, et notamment les ustensiles qui seront utiles pour le coiffer.

Lorsque ces objets sont enfin rassemblés, la troupe retourne au château d'Yspaddaden :

« Caw de Prydein se mit à lui raser la barde en enlevant tout, peau et chair, jusqu'à l'os, avec les deux oreilles en entier. Kulhwch lui dit :

'Homme, es-tu rasé ?

- Je le suis, répondit-il.

- Est-ce que ta fille est mienne, à présent ?

- Elle est tienne, dit le Géant. Et tu n'as pas à m'en remercier, mais tu dois remercier Arthur, qui te l'a procurée. S'il n'avait tenu qu'à moi, tu ne l'aurais jamais eue. Il est grand temps maintenant de me retirer de la vie.'

Goreu fils de Custenhin se saisit alors de lui par les cheveux, et le jeta derrière lui sur le fumier, il lui coupa la tête et la planta sur un pieu, en haut du rempart. »

La fin de ce conte médiéval, contenant la suite sans fin d'épreuves insurmontables, appartient au type AT 513A. On notera que Kulhwch est maudit, qu'il ne peut épouser qu'une femme précise, ce qui motive la quête.

La sorcière des Merveilles de Rigomer

Les Merveilles de Rigomer est un roman arthurien anonyme en vers, inachevé, datant du XIIIe siècle. Il n'est connu que par deux manuscrits, dont un ne contient qu'un court fragment. Le texte lui-même est inachevé et semble être l’œuvre d'un auteur qui ne savait trop où aller. Il est question d'un lieu d'Irlande, Rigomer, où tous les chevaliers qui ont tenté de se rendre sont maintenus prisonniers. Lancelot tente une première quête vers Rigomer, mais échoue. C'est Gauvain qui parviendra à déjouer les enchantements de l'endroit. Arthur, pour ne pas rester inactif, décide de partir à son tour, mais le roman s'interrompt avant d'en dire plus sur ce nouveau développement.

Il s'agit en fait d'une longue succession d'aventures et rebondissements, sans grand intérêt en tant que tel, si ce n'est qu'il a permis la conservation de nombreux motifs tirés du folklore. L'un des épisodes laisse apparaître un personnage du type qui nous intéresse.

Lancelot, à la recherche de Rigomer, est donc en Irlande et pénètre dans une grande et épaisse forêt. Il y trouve une maison, dans laquelle il rentre à cheval. Il voit alors, sur une natte de roseau, une horrible femme difforme, endormie. Son ronflement effraie le cheval de l'aventurier, qui renâcle et frappe des sabots, refusant d'avancer même sous les coups d'éperons. La femme se réveille alors et sans ouvrir les yeux, demande qui est là. Lancelot se présente comme un chevalier et accepte de se désarmer en échange de l'hébergement. Alors la vieille soulève ses paupières, énormes, dotées de coutices, terme rare, que l'on a traduit par crochets de fer mais auquel on a aussi donné le sens de « cordon, lacet, nœud ». Elle les suspend alors aux cornes qu'elle a sur le front.

Paradoxalement, elle se révèle hospitalière : elle confie le chevalier à sa nièce, une belle jeune femme, avec qui Lancelot passe la nuit. Le lendemain, Lancelot reprend sa route mais croise trois chevaliers. Hélas, il s'avère que la nièce de la vieille est l'amie de l'un d'eux. Aussi Lancelot doit-il les combattre, ce qu'il fait tour à tour. Les trois sont vaincus l'un après l'autre. On verra plus loin que ces trois chevaliers correspondent à trois dragons cavaliers, présents dans les contes d'Europe centrale et orientale, combattu avant la rencontre avec notre personnage.

Trote de Salerne

Le rapprochement entre cette vieille sorcière aux paupières qu'elle doit soulever et suspendre pour voir son interlocuteur, et le géant gallois Yspaddaden Penkawr a été étudié 1965 par Philippe Ménard, au détour d'une étude sur une autre sorcière, Trote de Salerne, mentionnée par Rutebeuf, laquelle « se fait un couvrechef de ses oreilles et ses sourcils lui pendent en chaînes d'argent sur les épaules » (« qui fait cuevrechiés de ses oreilles et li sorciz li pendent a chaaines d’argent par desus les espaules »). On a régulièrement mis cette description de Trote de Salerne, tout comme celle de la sorcière des Merveilles de Rigomer, sur le compte de l'humour, mais quoi qu'il en soit, il ne fait guère de doute, pour l'ensemble des commentateurs qu'il s'agit-là d'un emprunt à la mythologie celtique : on parle même d'un possible lai breton perdu.

Grand Sourcil

Un conte, appartenant au type AT 560, collecté par Paul Sébillot en Haute-Bretagne nous montre le fils d'un pauvre cordonnier partir à l'aventure et devenir capitaine de bateau. Sur une île, il est obligé de livrer tribut au roi des animaux, sous peine d'être dévoré par l'ensemble des bêtes. Puis :

« Le capitaine entra dans la forêt ; il marcha longtemps, mais quand vint la nuit, il n'en était pas encore sorti. Il se dit :

- Où vais-je me coucher pour ne pas être dévoré par les bêtes féroces ?

Il regarda de tous côtés, et vit un arbre qui lui sembla commode : il grimpa dedans et s'installa sur les branches de manière à ne pas tomber s'il s'endormait ; mais il ne ferma pas l'oeil de la nuit ; il aperçut une lumière à travers l'épaisseur des bois, et il pensa :

- Il faut qu'il y ait là quelque maison.

Au point du jour, il descendit de son arbre, et regarda à sa boussole dans quelle direction se trouvait la lumière ; c'était à l'ouest et il marcha de ce côté ; il alla bien loin et vit un gros rocher, gros comme une montagne et brillant comme le soleil. Il tourna autour, et découvrit une grande porte qui était ouverte. Quand il fut sur le seuil, il vit un vaste foyer, et auprès un gros chat noir qui se chauffait. »

Le héros se lie d'amitié avec le chat, qui lui dit que les lieux sont habités par le géant Grand-Sourcil, qui est magicien.

« Le grand géant Grand-Sourcil ne revenait à sa maison que le matin et le soir, jamais dans le cœur du jour. Le voilà arrivé ; il avait des sourcils qui lui tombaient jusqu'aux pieds, et quand il voulait regarder ou manger, il était obligé de les écarter de ses yeux. »

Le héros est découvert par le géant, qui veut d'abord le manger, puis le garde prisonnier. Puis il découvre dans la demeure de son hôte un anneau magique qui exauce tous les vœux. Le héros s'en sert pour s'échapper. Grâce à l'anneau, il acquiert fortune et épouse. Mais le géant se lance à sa recherche : il coupe ses sourcils pour pouvoir y voir et imagine un stratagème pour confondre son voleur. Mais à nouveau grâce au chat, tout est bien qui finit bien.

Nous avons ici un héros fils de cordonnier, or chez les Celtes, Lug, adversaire de Balor, entretient des liens étroits avec la cordonnerie. Au Pays de Galles, il est même un temps cordonnier. Le héros, chez le géant, est aidé par un chat.

Pays basque

Une légende collectée en 1917 concernant les Jentilak, de bons géants, bâtisseurs de mégalithes, dit :

« On dit que les Jentilak qui vivent dans la grotte de Leizai, virent dans le ciel une étoile d'une beauté singulière. En la voyant, les Jentilak prirent peur, et voulurent s'enquérir de ce qui allait se passer dans le monde. Ils allèrent chercher à l'intérieur de la caverne un vieillard aveugle, dont ils soulevèrent les paupières avec une pelle, et le placèrent à regarder le ciel, pensant qu'il saurait ce que signifiait cette étoile. Lorsqu'il la vit, il dit : « Ah, mes enfants ! Kixmi est né, nous sommes maintenant perdus. En raison de cela je me fracasserai dans le précipice. » Les Gentilak appelait Jésus-Christ Kixmi, et disait que ce mot signifie singe. Comme cela avait été dit, il se précipita dans le fond rocheux, et le vieil homme connu une mort douce. Puis le christianisme commença à se disperser de par le monde, et les Jentilak furent dispersées et perdues. »

Ainsi, le chef des Jentilak est le plus vieux d'entre eux, il est aveugle, vit dans une grotte, et pour voir l'étrange étoile qui annonce la venue du Christ (Kixmi) et donc la disparition de ces géants, on doit lui soulever la paupière avec une pelle. La confrontation du personnage avec un héros est donc ici particulièrement christianisée et remplacée par une confrontation indirecte avec le Christ.

Hongrie

La mère des dragons

Dans un conte hongrois traduit par Jeremiah Curtin et appartenant au registre du conte-type AT 300A propre à l'Europe de l'Est, Kiss Miklos et la fille verte du roi vert, il est question de trois jeunes hommes pauvres, à qui le roi de leur pays promet que celui qui pourra ramener le soleil et la lune lui succédera. Les trois frères se lancent donc en quête. Le cadet, bien que raillé par ses aînés, possède un cheval magique, né du vent. Arrivés à un pont d'argent, ils décident de faire halte, s'attendant à l'arrivé d'un dragon à douze têtes, porteur de la lune. Arrivé sur le pont, le cheval du dragon renâcle, et son maître est obligé de l'insulter. Le cadet combat le dragon et parvient à le vaincre. Ils reprennent leur voyage et arrivent à un pont d'or, où ils attendent cette fois-ci un autre dragon, porteur du soleil. La même scène se répète. Mais les têtes du dragon repoussent, quand bien même le héros frappe « comme la foudre ». Il en sort cependant vainqueur. Plus tard, il se transforme en petit chat gris et rencontre les deux épouses et la mère des dragons. Il apprend ainsi les pièges qu'elles lui préparent. Ainsi, concernant la vieille mère :

« The old woman [said] to her two daughters-in-law : 'My dear girls, just prop up my two eyes with that iron bar, which weighs twelve hundred pounds, so that I may look around.'

Her two daughters-in-law then took the twelve hundred-pound iron bar and opened the old woman's eyes ; then she spoke thuswise : 'If that cursed Kiss Miklos has killed my two sons, I will turn into a mouth, one jaw of which will be on the earth and the other I will throw to the sky, so as to catch that cursed villain and his two brothers, and grind them as mill-stones grind wheat.'

When the little gray cat had heard all this exactly, it shot away in a flash out of the cabin, sprang along, and never stopped till it came to the good magic steed. The old woman threw the twelve-hundred pound bar after the cat, but she failed in her cast, for that moment her eyelids fell ; she was not able to keep them open unless they were propped, for she was old. So Kiss Miklos escaped the twelve-hundred pound bar, - certain death. I say that he escaped, for he came to his good magic steed, shook himself, and from a little gray cat became a young man as before. Then he sat on the good steed, which sprang once, jumped twice, and straightway Miklos was with his two brothers ; then they fared homeward in quiet comfort. »

Par la suite, le héros parvient sans peine à déjouer les pièges tendus par les trois femmes : c'est notamment dans une forge qu'il parvient à battre la mère. Une fois rentré chez lui, il devint roi, mais connut encore de nombreuses aventures.

On voit ici une vieille sorcière, mère de deux dragons combattus par le héros, vivant dans une cabane et dotée, en raison de sa vieillesse, de paupières lourdes au point de nécessiter, pour être maintenues en place, le soutien d'une barre de fer de 1200 livres, barre mise en place par ses belles-filles. Il faut noter qu'il n'y a qu'une seule barre : un caractère cyclopéen de la sorcière n'est donc pas exclu.

Un autre conte hongrois, collecté chez des Tsiganes et d'un tout autre type (son éditeur l'attribue au AT 409b), montre un personnage assez similaire. Le héros est né de parents pauvres, et sa mère a fait vœu de le marier à une fille née de la rosée. À cause de cela, le fils quitte ses parents, en quête de sa promise. En chemin, il trouve un os, qui parle et l'invite à le prendre, puis il acquiert l'aide d'un poisson, qu'il n'a pas mangé après l'avoir pêché. Ensuite :

« He walks on and on, and was wandering continually for a week. An he reaches a house. Just a lamp is burning and who is inside, an old witch [bosorkana, du hongrois boszorkány]. And so, he (says) to her : 'Good day, you registered fucked whore !' But the witch to him : 'Thank you. That's right that you've spoken to me this way, otherwise I'd have eaten you, I'd have cut your head off to this block. But there is a pitchfork in the corner. Sitck it into my eyelashes so that I should see you ! Because I don't see you my lashes are too big.' Then gets to it the boy and goes to the corner, and takes the pitchfork and sticks it into the eyes of the witch. And the boy lifts the eyes of the witch. And that is done and the witch sees him. »

Par la suite, la sorcière demande au garçon ce qu'il fait-là : il lui répond qu'il est à la recherche de travail. Aussi lui en donne-t-elle, avec en premier lieu le nettoyage de son étable, à faire en moins de 24 heures, sous peine d'avoir la tête coupée. Mais il réussit, et découvre par hasard dans la maison une jeune fille, qu'il met dans sa poche et emporte en partant.

Ici, la sorcière est tout autant hostile que secourable. Elle tolère la présence du héros, et c'est chez elle que celui-ci trouve une épouse.

De ces sorcières hongroises, on donne aussi la description suivante :

« They grow so old that their lower lips hang down as far as their knees ; their eyelids also become elongated, so that if they wish to see anything the eyelid has to be lifted up with a huge iron rod, weighing 300 hundred-weights. »

Chez les Slaves

En Bulgarie

C'est très curieusement le « Pape de Rome » (Rim-papa), qui, en Bulgarie, est associé à notre motif. On dit de lui, notamment, qu'il est immortel, qu'il dort constamment, mais qu'à intervalles réguliers (selon les versions, tous les ans, trois ans ou cent ans), des gens viennent avec des fourches soulever ses paupières : il peut alors voir, et si tout va bien dans le monde, il se rendort.

En Ukraine

En Ruthénie subcarpathique, dans la région de Zemplín, chez des Ukrainiens de Slovaquie donc, le héros d'un conte du type AT 303 mais très proche du premier conte hongrois vu ci-dessus, après avoir tué trois dragons, rencontre sa mère, qui n'est autre que la version locale de la baba Jaga, Hinžibaba. Or elle aussi a besoin de fourches de fer pour soulever ses paupières. Le héros parviendra à la vaincre dans une forge.

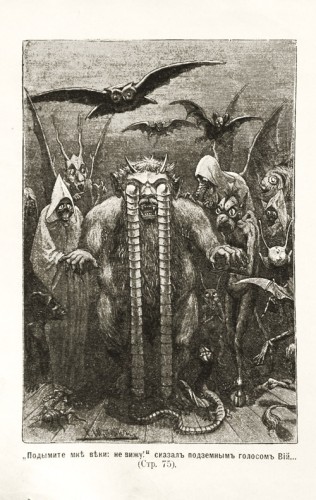

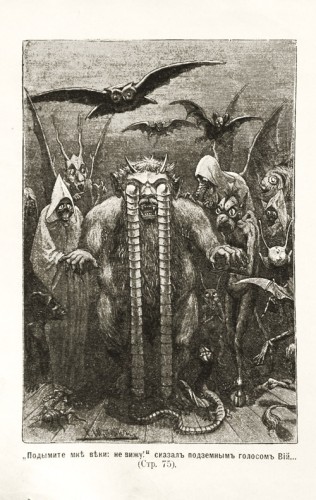

Vij. Gravure de R. Stein, 1901

Un peu plus à l'Est, le personnage de Vij re-créé par Nicolas Gogol, monstre qui réclame qu'on lui soulève ses paupière afin de pouvoir voir un diacre qui se tient dans un cercle magique, réemploie en fait un conte-type bien connu, AT 307 (« La princesse dans le suaire ») et un motif associé dans les traditions populaires à divers personnages: Bunjak, Bunio, Kasjan (saint Jean Cassien). Dans certains cas (Bunio), des fourches sont nécessaires pour découvrir les yeux, dans d'autres (Kas'jan), c'est une force maléfique ou un esprit mauvais. Le cas de Bunjak, tel qu'il a été publié au XIXe siècle en tant que légende locale de Podolie, est intéressant. Bunjak est un personnage légendaire, mais il tire sa source du khan couman Bonyak, qui au tournant du XIIe siècle, mena plusieurs raids contre la Rus' de Kiev :

« Selon les récits des anciens habitants, il se trouvait, au village de Velikaja Kuželeva, les restes d'une ancienne place forte nommée Mistysko, qui était dominée par une ville nommée Kružel. A cette époque-là, cette ville fut mise à sac par un Cosaque nommé Soludyvij Bunjak, qui mit aussi à sac le village. C'est actuellement le village de Tyškov qui se trouve à la place de l'ancien village, et la ville de Gorodisko à la place de la ville. Bunjak cessa ses aventures militaires de brigand près d'un faubourg nommé Gorodok (Hrudka), du district Kamenetski, où il fut offensé par un tanneur nommé Samson Kirilovič. Ce tanneur était si fort que lorsqu'il s'emportait et se fâchait contre quelqu'un, il pouvait déchirer ce dernier en douze morceaux de peau de bœuf.

Au moment où Bunjak s'approchait de Gorodok avec son armée, le tanneur dormait. Les habitants le réveillèrent et lui demandèrent de les défendre. Le tanneur ordonna de faire un épais ruban de soie. Il attacha une meule de moulin au ruban, et faisant des mouvements circulaires, il anéantit toute l'armée de Bunjak, ainsi que ce dernier. Cela se passa ainsi : le Cosaque Bunjak avait des paupières qui pendaient jusqu'à terre. Lorsqu'il s'approchait d'une ville, deux Cosaques soulevaient ces paupières à l'aide de fourches spéciales. Alors Bunjak observait la ville et montrait à son armée où il fallait commencer l'assaut. Ces paupières avait pour propriété que si quelqu'un parmi les ennemis de Bunjak était suffisamment fort et pouvait les soulever, alors il triomphait de Bunjak. Cette tâche incomba au tanneur Kirilovič, qui profita de cette mystérieuse propriété des sourcils, les souleva et vainquit Bunjak, et donc fit cesser les conquêtes destructrices de ce dernier. De ce fait, le village de Gorodok échappa à la destruction et demeure intact jusqu'à nos jours. »

Le héros est ici non pas un cordonnier, comme dans les textes celtiques, mais un tanneur, ce qui est très proche. Bunjak, comme Balor, attaque avec une armée. Comme en Irlande, son regard affaiblit l'adversaire, non pas à l'aide d'un pouvoir réellement magique, mais en indiquant à ses troupes le point faible de la ville à prendre. Le héros est endormi, au début du combat, tout comme Lug l'est dans sa prison. Il s'avance vers l'ennemi avec une meule en pierre attachée à un ruban de soie : Lug s'avance vers l'ennemi avec ses chaînes de lin au bout desquelles pendent des pierres. Enfin, les deux maîtrisent la puissance de l'oeil de leur adversaire.

Le folklore ukrainien concernant Bunjak ou Bunjaka est riche, et parfois contradictoire.

Une légende prenant place à Kiev fait de Kirilo Kožum'jaka (Kirill le Tanneur), visiblement un autre nom de Samson Kirilovič, le héros du conte-type AT 300 : il délivre et la ville, et la fille du roi, d'un terrible dragon. On dit que c'est un sorcier, parfois qualifié de « tatar », et que son foie est placé dans la partie haute de son cœur, et que de ce fait il suffit de couper cet organe pour qu'il s'en aille, vaincu.

Il'ja Muromec en Biélorussie

En Biélorussie, c'est un conte lié à l'équivalent local d'Il'ja Muromec qui met en œuvre un tsar nommé Pražor (« Glouton »), et son serviteur Sokal (« Faucon ») :

« 'Qu'est que tu voudrais, Illiuška?

– Allons purifier le monde, tuer le sale Sokal!'

Et il demande à ses parents de le bénir:

'Ma mère et mon père, bénissez-moi, je vais dans le monde!'

Le père dit:

'Dieu te bénit et nous aussi. Tu peux aller ou tu veux et où Dieu te bénit!'

Alors, Illiuška a mis une selle d'or sur son cheval, a pris ses armes: la massue et la lance, et il est parti dans le monde. Il a voyagé pendant trois jours et il est arrivé dans le royaume du tsar Pražor. Il mangeait dix personnes par jour et le sale Sokal les lui apportait. Quand ce sale Sokal sifflait, les gens qui se trouvaient dans un rayon de douze verstes tombaient: il était tellement fort. Et il apportait les dix personnes par jour au tsar Pražor. Ce sale Sokal était assis seul sur douze chênes, et il avait douze cornes. Quand Illiuška s'est approché de lui, Sokal lui a dit:

'Bonjour, Illiuška, brave garçon! Pourquoi es-tu venu ici?

– Par la volonté même de brave garçon!'

– Alors, Illiuška, qu'allons-nous faire: nous battre ou nous réconcilier?'

Il avait peur, sachant qu'il pouvait y laisser la tête. Illiuška dit:

'Ce n'est pas pour me réconcilier que je suis venu mais pour me battre avec toi!'

Alors, il a crié comme un brave garçon, et a sifflé comme un cosaque:

'Bénissez-moi, Dieu et tous mes parents, ma mère, mon père pour m'aider et mon cheval parce que je vais faire la guerre au sale Sokal!'

Alors, Illiuška a saisi la massue et l'a frappé sur la tête, et l'a tué sur place. Il a coupé sa tête et l'a mise sur sa lance,il a coupé son corps en petit morceaux, l'a mis sur un tas de bois de tremble et l'a brûlé. Il a crié comme un brave garçon et a sifflé comme un cosaque:

'Alors, mon cheval, allons chez le sale tsar Pražor!'

Et ils sont partis, avec la tête de Sokal sur la lance. Ils y arrivent et posent la tête du sale Sokal en-dessous du perron du tsar. Le tsar Pražor a entendu quelqu'un arriver et a dit:

'Qui vient? Qui donc mon sale Sokal a-t-il laissé passer?'

Il ne savait pas que la tête de son sale Sokal est sur la lance, sous son perron!

'C'est moi qui vient, dit Illiuška! Tu auras le même sort que ton Sokal! dit il au tsar Pražor.

Et le tsar était très gros; ses yeux étaient bouffis de graisse et ses sourcils broussailleux et il ne voyait rien. Alors, il dit:

'Mes serviteurs fidèles, soulevez mes sourcils avec les fourches!'

Il voulait regarder Illiuška. Et le brave garçon Illiuška a pris sa massue et venait déjà vers lui, même le plancher craquait sous lui. Le tsar Pražor demande:

'Où est donc mon Sokal?'

Illiuška a bondi sur le plancher, a pris sa lance et l'a montrée au tsar et a dit: 'c'est ici qu'est ton Sokal!'

Le tsar Pražor a dit:

'Mes serviteurs fidèles! Donnez-nous à manger et à boire. Nous allons manger et boire avec Illiuška!'

Le tsar a ordonné de préparer un fauteuil en or pour Illiuška et de le mettre à côté de lui. Illiuška n' a rien voulu, ni manger, ni boire avec lui, sans rien dire, il a vite enlevé son chapeau de douze pouds et en a frappé le sale tsar Pražor de telle façon qu'il s'est enfoncé dans le mur en pierre de trois archines et le tsar est passé à travers ce mur. Il a tué le sale Sokal et le tsar Pražor et a purifié le monde. »

Ici nous voyons d'abord Il'ja combattre Sokal, l'équivalent de Solovej Razbojnik (dont le nom assone curieusement avec celui de Soludyvij Bunjak), combat durant lequel, ordinaire, son cheval est effrayé par le cri du monstre et renâcle. Ce motif, cependant, n'est pas présent ici.

Divers contes russes

Notre personnage reste bien présent dans les contes russes, notamment dans la collection d'Alexandre Afanassiev. Ainsi, dans La fille-roi 2 (AT 400), dit-on ceci :

« Alors le tsariévitch Vassili enfourcha son cheval et s'en fut, par-delà trois fois neuf pays, dans le trois fois dixième état. [...] Il gagna le royaume des lions. Le roi-lion dit : 'Hola, mes sept enfants! Prenez les fourches de fer pour me soulever les paupières, afin que je puisse regarder ce vaillant gaillard!' Il le vit, le reconnu et se réjouit'. »

Le roi-lion, qui n'est ici que bénéfique (même s'il rappelle le roi des animaux du conte breton), a toutefois besoin de ses sept enfants pour soulever à l'aide de fourches de fer ses paupières et voir le héros.

Toujours à l'est de la Russie, dans la région de Viatka (actuellement Kirov), un autre conte, en fait une byline mise en prose, montre comment les bogatyrs Aleša Popovič et Dobrynja Nikitic humilient la tsar païen Idol Idolic (semble-t-il une version particulière d'Idolišče), après avoir envoyé des flèches directement dans sa chambre. Ce tsar, monstrueux, est surpris de leur visite impromptue, et demande : « Apportez ces sept fourches, soulevez mes sourcils : je veux les voir. » Mais les deux preux ligotent le géant et le force à rendre hommage au tsar.

C'est cependant avec le conte d'Ivan Bykovič (« Jean fils du Taureau »), que j'ai pu mener jusqu'ici les comparaisons les plus fructueuses. Celui combine les types AT 300A et AT 513A. Un tsar n'ayant pas d'enfant parvient enfin à en obtenir grâce au roi des poissons : son épouse, sa cuisinière et sa vache tombent enceintes, et chacune donne naissance à un garçon, mais seul le cadet, Ivan Bykovič, aura une vraie stature de héros. Ils décident de partir découvrir le monde, et le cadet combat successivement trois dragons, dont le cheval se cabre à son approche, et qu'il parvient à vaincre. Il déjoue ensuite les plans de la mère et des épouses des dragons, mais la vieille mère parvient finalement à l'enlever et à l'emmener dans un souterrain :

« La sorcière, elle, avait entraîné IvanBykovič dans un souterrain et elle l'avait conduit à son mari, un vieux tout décrépit : 'Tiens, lui dit-elle, voilà celui qui nous a tous perdus !' Allongé sur un lit de fer, le vieux ne voyait rien : de longs cils et des sourcils épais lui bouchaient entièrement les yeux. Il appela douze puissants bogatyrs à qui il ordonna : 'Prenez les fourches de fer pour soulever mes sourcils et mes cils, afin que je voie quel genre d'oiseau a tué mes fils !' Avec des fourches, les douze costauds lui soulevèrent cils et sourcils. Le vieux put alors regarder. »

Le vieux va alors demander à Ivan de lui ramener une nouvelle épouse, la tsarine aux boucles d'or, ce qui ne sera possible qu'au prix d'épreuves insurmontables. Mais en chemin, le héros se fait de nouveaux compagnons : il conquiert l'épouse, revient chez le vieux, mais au lieu de la lui donner, il le tue et se marie avec la tsarine aux boucles d'or.

Dans les pays baltes

Dans son étude sur les corrélats folkloriques du Vij de Gogol, Christine Shojaei Kawan mentionne deux versions lettones du conte-type AT 307 contenant notre personnage. Je n'ai pu me procurer qu'une seule d'entre elle, un conte très proche de la nouvelle de Gogol, où, au final, les démons introduisent leur père dans la grange où se trouve le héros, un père si vieux qu'il est doté de grands sourcils :

« Quand le diable eut scruté la grange sans trouver le garçon, alors il ordonna à pleine voix : 'Mes fils, prenez une fourche et soulevez mes sourcils. Alors, je le verrai quand même ! »

De fait, le héros est repéré, mais il parvient, après diverses péripéties, à s'en sortir.

En Italie

Maudit pour avoir brisé des œufs dans un panier, un jeune berger héros du conte A bela Bargaglina de tre meje chi canta, collecté dans la région de Gênes, est condamné à rester tout petit tant qu'il n'aura pas rencontré et épousé la belle Bargaglina aux « trois pommes chantantes ». Aussi le berger se met-il en quête.

« The shepherd set out. He came to a bridge, on which a little lady was rocking to and fro in a walnut shell.

'Who goes there ?

- A friend.

- Lift my eyelids a little, so I can see you.

- I'm seeking lovely Bargaglina of the three singing apples. Have you any news of her ?

- No, but take this ivory comb, which will come in handy. »

Le garçon empoche l'objet et continue sa quête. Il rencontre ainsi successivement plusieurs personnages qui chacun lui donneront quelque chose à même de l'aider dans son voyage.

Il s'agit du conte-type AT 408, « Les Trois oranges ». Notre motif semble ici intrusif, car il est totalement absent des quatre autres versions collectées dans la même région, publiée par Andrews, qui ne parlent que de « petites dames », ou de « vieilles ».

En Grèce

Un conte collecté à Lesbos, du type AT 425 (« La recherche de l'époux disparu »), montre une jeune femme pauvre s'en aller par les chemins à la recherche de son époux disparu :

« On and on she went, and for a whole year saw neither man nor sheep, and fed like a beast on grass and herbs. At the year's end she came to a place with trees and a dry pond, and in the mud lay an ogress, with her eyelid hanging down over her face. Taking a piece of wood, the girl inserted it under the eyelids, and cut them short with her axe ; then she threw water over the ogress' face, and ran away and hid behind a tree. The ogress had been blind for fifteen years, and when she found her blindness cured, she called out : « Come here, whoever you are ! If you are a woman I will make you a queen, and if you are a man I will make you a king.' But the girl waited in hiding, and only came out when the ogress swore by her strength not to hurt her. The the ogress asked her what she wanted, and the girl said, 'I am looking for Melidoni.' 'Stay with me to-night,' said the ogress. 'I have two sisters, and we have on son between us, and when he comme home to-night I will ask him and we will see if he can tell.' The she turned her into a button and put her in her pocket. »

Finalement, l'ogresse indique à la jeune fille le chemin pour se rendre chez sa sœur, et la scène se répète. La jeune fille rencontrera ainsi trois ogresses avec leurs familles.

Le domaine sémitique

Le Talmud de Babylone

Le Talmud de Babylone est notre plus ancienne source mentionnant notre type de personnage monstrueux. Il s'agit ici du célèbre rabbin Johanan ou Yochanan, qui vécut durant le IIIe siècle après J.-C. L'épisode prend place lors d'une rencontre avec le rabbin Kahana, venu de Babylone à Jérusalem :

« A certain man who was desirous of showing another man's straw [to be confiscated] appeared before Rab, who said to him: ‘Don't show it! Don't show it!’ He retorted: ‘I will show it! I will show it!’ R. Kahana was then sitting before Rab, and he tore [that man's] windpipe out of him. Rab thereupon quoted: Thy sons have fainted, they lie at the heads of all the streets as a wild bull in a net; just as when a ‘wild bull’ falls into a ‘net’ no one has mercy upon it, so with the property of an Israelite, as soon as it falls into the hands of heathen oppressors no mercy is exercised towards it. Rab therefore said to him: ‘Kahana, until now the Greeks who did not take much notice of bloodshed were [here and had sway, but] now the persians who are particular regarding bloodshed are here, and they will certainly say, "Murder, murder!"; arise therefore and go up to the Land of Israel but take it upon yourself that you will not point out any difficulty to R. Johanan for the next seven years. When he arrived there he found Resh Lakish sitting and going over the lecture of the day for [the younger of] the Rabbis. He thereupon said to them: ‘Where is Resh Lakish?’ They said to him: ‘Why do you ask?’ He replied: ‘This point [in the lecture] is difficult and that point is difficult, but this could be given as an answer and that could be given as an answer.’ When they mentioned this to Resh Lakish, Resh Lakish went and said to R. Johanan: ‘A lion has come up from Babylon; let the Master therefore look very carefully into to morrow's lecture.’ On the morrow R. Kahana was seated on the first row of discip les before R. Johanan, but as the latter made one statement and the former did not raise any difficulty, another statement, and the former raised no difficulty, R. Kahana was put back through the seven rows until he remained seated upon the very last row. R. Johanan thereupon said to R. Simeon b. Lakish: ‘The lion you mentioned turns out to be a [mere] fox.’ R. Kahana thereupon whispered [in prayer]: ‘May it be the will [of Heaven] that these seven rows be in the place of the seven years mentioned by Rab.’ He thereupon immediately stood on his feet and said to R. Johanan: ‘Will the Master please start the lecture again from the beginning.’ As soon as the latter made a statement [on a matter of law], R. Kahana pointed out a difficulty, and so also when R. Johanan subsequently made further statements, for which he was placed again on the first row. R. Johanan was sitting upon seven cushions. Whenever he made a statement against which a difficulty was pointed out, one cushion was pulled out from under him, [and so it went on until] all the cushions were pulled out from under him and he remained seated upon the ground. As R. Johanan was then a very old man and his eyelashes were overhanging he said to them, ‘Lift up my eyes for me as I want to see him.’ So they lifted up his eyelids with silver pincers. He saw that R. Kahana's lips were parted and thought that he was laughing at him. He felt aggrieved and in consequence the soul of R. Kahana went to rest. On the next day R. Johanan said to our Rabbis, ‘Have you noticed how the Babylonian was making [a laughing-stock of us]?’ But they said to him, ‘This was his natural appearance.’ He thereupon went to the cave [of R. Kahana's grave] and saw a snake coiled round it. He said: ‘Snake, snake, open thy mouth and let the Master go in to the disciple.’ But the snake did not open its mouth. He then said: ‘Let the colleague go in to [his] associate!’ But it still did not open [its mouth, until he said,] ‘Let the disciple enter to his Master,’ when the snake did open its mouth. He then prayed for mercy and raised him. He said to him, ‘Had I known that the natural appearance of the Master was like that,I should never have taken offence; now, therefore let the Master go with us.’ He replied, ‘If you are able to pray for mercy that I should never die again [through causing you any annoyance], I will go with you, but if not I am not prepared to go with you. For later on you might change again.’ R. Johanan thereupon completely awakened and restored him and he used to consult him on doubtful points, R. Kahana solving them for him. This is implied in the statement made by R. Johanan: ‘What I had believed to be yours was in fact theirs. »

Ici le rabbin Johanan n'est pas maléfique, il se pose plutôt comme un bon maître, mais fait l'objet d'une confrontation avec un savant visiteur, ce qui l'oblige à demander à ses serviteurs de soulever ses paupières (ou ses sourcils selon les traductions) à l'aide de pinces cosmétiques d'argent : si les sourcils du rabbin restent extraordinaires, le moyen de les relever se fait ici beaucoup plus rationnel.

Des goules algériennes et palestiniennes

Un conte arabe algérien montre un personnage dont les sourcils gigantesque sont uniquement dus à sa vieillesse (« un vieillard très âgé dont les sourcils, à cause de sa vieillesse, retombaient sur son visage »).

Un autre conte algérien, très similaire, multiplie ces vieillards au cours d'une quête héroïque d'épouse pour un prince, et fait de ceux-ci des goules, trouvées chaque fois au fond d'un trou recouvert d'une dalle, et qu'il faut raser pour obtenir d'eux des renseignements pour la suite de la quête du héros :

« Ils remontèrent sur leurs chevaux et cheminèrent jusqu'à ce qu'ils rencontrèrent, sous une tente en toile un vieillard de race humaine qui gardait des chameaux. 'Vieillard, nous sommes venus pour t'interroger sur le Roi à la botte jaune. — Sans doute, jeunes gens, vous avez fait marché de votre vie. A partir d'ici, vous ne rencontrerez plus sur votre chemin que les Ghouls les épouvantables : si vous n'êtes intrépides et sûrs de vous, revenez sur vos pas. — Nous sommes résolus. — Attendez : je vais vous donner un rasoir, un peigne et un miroir. Suivez mes instructions. Ce sont les Ghouls qui vous indiqueront le chemin. Toutes les fois que vous trouverez une dalle, gardez-vous de passer outre. Vous la soulèverez et vous vous enfoncerez sous terre. Vous trouverez un vieillard dont les sourcils seront si touffus qu'ils cacheront ses yeux. Vous le saluerez poliment. Il vous dira : 'J'ai le poil long : rasez-moi'. Vous le ferez. Alors seulement vous l'interrogerez. Et, en le quittant méfiez-vous : tenez l'épée dégainée. Point de sommeil. »

Le même type d'enchaînement apparaît dans un conte palestinien, du type AT 327B, où il est question d'un homme en quête de deux grenades qui leur permettront, à lui et à sa femme, d'avoir des enfants :

« The man went forth, and came upon the ghoul. He approached him immediately, shaved his beard, trimmed his eyebrows, and said : 'Peace to you !'

'And to you, peace !', replied the ghoul. 'Had not your salaam come before your request, I would've munched your bones so loud my brother who lives on the next mountain would've heard it. What do you want ?' »

Le héros va ainsi rencontrer trois ghouls, avant de trouver leur mère qui lui indiquera où se trouvent les grenades.

Le même motif réapparaît encore, toujours en Palestine, dans un autre conte qui combine les types AT 314 et 590, ainsi que dans un conte égyptien lié aux Mille et une nuits (mais sans qu'on soit sûr qu'il soit ancien), de type AT 707, qui substitue aux goules un derviche. Ce conte, introduit pour la première fois au corpus des Mille et une nuits par Antoine Galland, connaîtra une diffusion importante, notamment en Europe, grâce à des livrets de colportages : j'aurai à revenir sur ce point important.

On notera cependant que ces contes s'éloignent de notre motif : s'il est bien question de sourcils qui masquent la vue, il n'est plus question de les soulever – encore moins de les faire soulever par un tiers – mais simplement de les coiffer. Cependant, on peut penser que l'idée était présente anciennement. En effet, un conte kabyle, présentant toujours un épisode très similaire à ceux des contes ci-dessus, nous dit ceci :

« Il vit un vieillard assis, dont les sourcils étaient si longs et si épais qu'il ne pouvait rien voir. Le jeune homme immédiatement sortit son couteau et trancha les sourcils d'une des yeux du vieux. Étonné, celui-ci leva la tête et dit : 'Quoi ? Ainsi ressemble le monde dans lequel je me trouve ? Ah, voilà comment le monde est ? Je t'en prie, coupe également les sourcils de l'autre côté, que je puisse donc voir de mes deux yeux !' Le garçon répondit : 'Je veux bien le faire, mais vous devez me jurer que vous me montrerez la maison de Chtaf Larais.' Le vieil homme dit : 'Je jure par Dieu que je te montrerai la maison de Chtaf Larais, une fois que tu m'auras coupé les sourcils de l'autre côté, quand je pourrai voir et observer parfaitement.' Le jeune garçon coupa alors les sourcils de l'autre côté. Le vieil homme était maintenant en mesure de voir comme tout le monde, et montra alors au jeune où se trouvait la maison de Chtaf Larais. »

Ici, il n'est plus question d'une goule ou d'un derviche, mais d'un vieil homme, dont les sourcils tombent jusqu'au menton. Et si d'emblée le héros commence à le coiffer, comme dans les contes arabes, il ne le fait qu'à moitié, et le vieux doit insister. On retrouve alors une forme très proche de la formule présente dans les contes européens : « Je te prie te me couper aussi les sourcils de l'autre côté, afin que je puisse voir ». Et c'est seulement après un échange de garanties que le héros accepte. En contrepartie, le vieil homme lui indique le chemin pour la suite de sa quête.

En Asie et en Sibérie

Il faut passer de là directement au bouddhisme chinois et à son culte pour le disciple du Bouddha nommé Pindola Bhāradvāja pour retrouver un personnage semblable. Celui-ci est décrit, dans une source chinoise concernant le moine du IVe siècle Daoan comme ayant des cheveux blancs, et des cils blancs si longs qu'ils pendaient et couvraient les pupilles de ses yeux au point qu'il devait s'aider de ses mains pour y voir. C'est là un signe de grande vieillesse, mais aussi de clairvoyance.

Plus au nord, en Sibérie centrale, autour du Ienesseï, on a collecté chez les Ket un conte qui met en présence un héros récurant, Kas'ket, avec une sorcière nommée Dootam et qui ressemble beaucoup à la Baba Yaga russe. Prisonnier chez elle, le héros finit par grimper dans un arbre. La sorcière recrache cependant une hache, qu'elle a avalé en même temps qu'un bûcheron, et commence à couper l'arbre. Mais Kas'ket se fait aider par un lièvre :

« Elle [Dootam] lui rendit une hache et s'allongea pour se reposer. Le lièvre prit la hache et enfonça dans l'arbre les éclats de bois que Dootam avait coupés.

'Mamie, l'arbre est tombé', cria le lièvre avant de s'enfuir.

Dootam bondit :

'Mon petit lièvre, rends-moi ma hache, rends-moi ma hache !, criait-elle. Kas'ket, descends ici, chez ta mamie !

- D'abord, allonge-toi au pied de l'arbre, étends ta bouche et agrandis tes yeux à l'aide d'un petit bâton !'

Elle se coucha.

'Reste comme ça, je vais sauter auprès de toi !'

Lui-même descendit un peu et resta assis. Il avait de petits cailloux dans sa poche. Il s'en servit pour boucher les yeux de Dootam. Cette dernière se mit à se rouler ! Il sauta en bas, la frappa avec un épieu et la tua. Il fit un grand feu de bois mort et l'y brûla. »

Le motif apparaît ici comme un vestige : il n'est pas dit que Dootam a de grands sourcils ou de grandes paupières, mais elle est tout de même obligée par Kas'ket de maintenir ses yeux ouverts à l'aide d'un bâton.

Chez les Daur, en Mongolie intérieure (Chine), un conte du type AT 300A (mais avec des emprunts de motifs relevant d'AT 302) a été noté. Le héros, qui possède un cheval merveilleux, se voit contraint par sa mère d'épouser la fille d'un monstre, une sorte de dragon à plusieurs têtes. Le héros, avec l'épée de son père, tue le monstre, puis arrive à la maison de sa femme :

« When they reached the courtyard, the boy tied Gold to the poplar and went inside, where he found a hideous black woman sitting on a kang. Her upper eyelid hung down over her face and her lower eyelid hung down to her breasts. When she heard someone in the house, she pulled up her upper eyelid with a stick, raised her head, and said angrily, 'You have rejoiced too early. I have more than ten times my dead husband's power'. »

Il se trouve que cette femme hideuse cache son âme dans un peuplier, non loin de sa maison : le cheval va alors le fouler au pied, ce qui lui permettra de la vaincre, plus tard, lors d'un combat dans un lac.

En Sibérie méridionale, les Touvines (région de Touva, donc), connaissent notre personnage. Dans un conte populaire difficile à classer, ayant pour héros un certain Er-Sarug, on voit celui-ci s'engager dans un région de la forêt qui lui était jusqu'ici interdite par sa mère, son père y ayant disparu. Il y rencontre plusieurs vieux, avant d'arriver jusqu'au Khan, qui était laid car ayant une paupière tombant sur le nez, qu'il souleva pour regarder le héros. Il lui impose diverses tâches, envoyant même ses sept fils contre lui, mais en définitive, Er-Sarug parvient à épouser sa fille.

C'est un récit assez proche que propose une épopée yakoute concernant le héros fondateur Er-Sogotox : celui-ci désire prendre pour épouse la fille d'un abaasy, un démon. Celui-ci, pour voir son potentiel gendre, soulève ses paupières à l'aide de crochets de fer. Il clame alors son refus : Er-Sogotox est contraint de se battre contre le frère de sa fiancée, mais il gagne.

Un vieux brigand du même type que le Khan touvine est connu chez les Bouriates, mais avec une légende bien moins développée. Ses sourcils tombent jusqu'à sa poitrine. Chez ce même peuple, Eme-Xara-mangatxaj est une créature féminine monstrueuse, noire, qui rappelle certaines sorcières de contes russes, et notamment la mère des dragons vue ci-dessus : sa bouche, une fois ouverte, touche le ciel. Un héros, après avoir vaincu le fils de ce monstre, convoite une jeune fille de son entourage. Un conte nous donne alors une description de la créature :

« En arrivant dans le premier palais de cuivre, il mis pied à terre et entra dans le palais. Là, se trouvait une seule femme noire, Eme-Xara-mangatxaj, à la peau fripée. Cette femme avait les paupières supérieures qui tombaient sur le nez, et les paupières inférieures qui tombaient sur les joues. Sa lèvre supérieure arrivait sur sa mâchoire, et sa lèvre inférieure sur sa poitrine. Quant à son ventre, il lui arrivait aux genoux. Eme-Xara-mangatxaj était une terrible femme. Elle souleva ses paupières supérieures à l'aide d'un arbre épais comme un pilier. »

Elle lance alors des menaces au héros, et le combat s'engage, un combat de trois ans, au bout duquel elle sera vaincue et son corps brûlé.

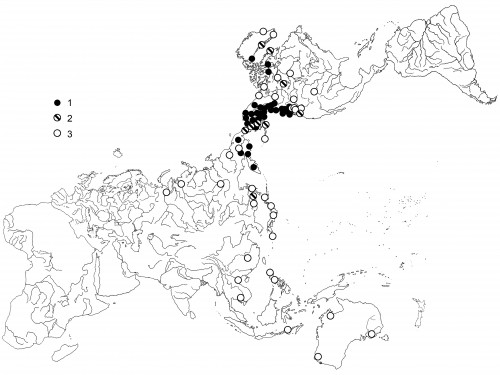

Les Amériques

Cette donnée asiatique est donc très isolée, et il faut franchir le détroit de Behring pour retrouver nos personnages dans divers contes amérindiens ou dans des contes collectés auprès de population d'origine européenne.

En Colombie britannique

En Colombie Britannique, on a collecté à Fort Frazer un conte intitulé La femme qui se maria avec un grizzly, qui n'est pas, contrairement à ce que le titre pourrait faire croire, une version de Jean de l'Ours. Ici, un des nombreux héros de ce conte foisonnant, nommé Ahlnuk, rencontre un vieillard qui coupe un tronc d'arbre. Il va le voir et lui demande :

« 'Grand-père, que fais-tu ?' - 'Je fabrique une massue pour tuer Ahlnuk', répondit le vieil homme, se retournant et soulevant ses paupières avec ses doigts pour voir qui le questionnait. »

Et aussitôt Ahlnuk tue le vieil homme.

Dans le même secteur, chez les Salish de l'Upper Thompson, deux versions du même conte, Wolf-Boy, ont été collectées, et dans toutes deux, le héros est aidé de sa grand-mère, une créature qui semble bien appartenir à l'Autre-Monde : celle-ci est officiellement aveugle, mais dotée de grands talents de vision. Cependant, il faut soulever ses paupières à la main. Le héros et sa grand-mère sont les uniques rescapés d'un massacre du à des créatures étranges. Elle a pu sauver son petit-fils en s'installant pour vivre dans un trou. Une fois devenu adulte, Wolf-Boy demande ce qui s'est passé et décide d'aller à la découverte du monde : il taille un tronc d'arbre en forme de canot, dans lequel il place sa grand-mère. La deuxième version du conte rapproche singulièrement cette grand-mère de Balor :

« Wolf-Boy set out with his grandmother to attack the enemies who had killed his people. They travelled north to where their enemies lived. He dragged his grandmother in a hollow log. There were four stages or obstacles on the way. They came to a large lake. Wolf-Boy said to his grandmother, 'There is nothing but water ahead of us, we cannot proceed.' The old woman took off her belt and whipped the water. She threw her belt out over the surface of the lake, and thus cut the water. As she drew in the belt, the water divided in two where the belt had touched it. Thus Wolf-Boy dragged his grandmother over the dry bottom of the lake. When they had passed, the water closed up behind them. They came to other obstacles, and Wolf-Boy told his grandmother. She requested him to lift up her eyelids, so she could see. As soon as she looked at the obstacle, it disappeared. They seemed to have shot forward at once to a place beyond it, or as far as the old woman's glance had penetrated; or the earth contracted, and the obstacle was left behind. »

Dans la première version, alors qu'ils arrivent près du village de leurs ennemis, Wolf-Boy prend la forme d'un loup et commence à faire le tour des maisons. Wolf-Boy met alors le feu au village.

Chez les Iroquois

Plus à l'Est, chez les Iroquois Seneca, le héros d'un conte, à la recherche de tabac, entre dans une maison où il trouve un vieillard nommé Longs-Sourcils. Trois fois, il le questionne pour savoir s'il en a, et le vieillard ne répond pas. Le héros le frappe et seulement alors le vieillard soulève ses cils pour voir qui s'adresse à lui.

Chez les Hopi

Plus au Sud, chez les Hopi, il est question dans un conte d'un homme nommé Hásohkata, qui avait des paupières qui tombaient sur sa poitrine, et qu'il devait soulever pour voir :

« So he [le héros] traveled westward, kicking before him his ball. All at once the ball disappeared and he found that it had dropped into a kiva. He approached the kiva and waited outside. All at once some one called from within, saying, that he had been seen and that he should come in, as nobody would hurt him. So he went in and found that his ball was lying north of the fireplace. He was again, with the utmost kindness, invited to sit down, with which he complied. He thought that those who lived here could by no means be called dangerous or bad. The man living in the kiva had long eyelids that were hanging down on his breast and that had to be laid back over his head when he wanted to see. His name was Hásohkata, and soon he said: 'Now, let us play totólospi.' The young man consented, but Hásohkata beat him twice. 'What will you pay me now?' he asked the young man. 'I do not know,' the latter said, 'I have nothing. You may take my ball, however.' 'I do not want that,' Hasohkata said, 'but you may lie down outside at the entrance of my kiva and it will not be so cold then', for it had by this time become fall and the weather was getting cold. The young man consented, but Hásohkata said to him: 'I am afraid you will run away then, so I am going to tie your hands and feet,' which he did. In a little while the young man began to feel very cold while he was lying outside of the kiva. »

Plus tard, le héros est délivré par sa grand-mère, nommée « Femme-Araignée », qui, comme la Baba Jaga russe, commande aux animaux et obtient leur aide : le vieil homme maléfique est tué et dévoré par eux.

Au Nouveau-Mexique et en Gaspésie

Notre personnage réapparaît au Nouveau Mexique, dans un conte d'origine espagnole intitulé El Pájaro verde (L'Oiseau vert). Il y est question d'une jeune fille à la recherche de ses deux frères qui vient à rencontrer un vieil homme:

« After walking all day long, she came to a little cabin at the foot of a very high mountain. She was very tired, so she knocked on the cabin door, hoping to find a place to sit down and rest. Nobody answered, so she knocked again, but finally opened the door et walked in. There, on an old bed in a corner of the room, was an old, old man with a beard that reached to his knees, and eyebrows and eyelashes that reached to his chin. He tried to speak, but the beard was so heavy that he could not speak. Noticing that the old man was trying to tell her something, María took a pair of scissors and cut his beard so he could talk. She asked him first if he had seen her two brothers, and the old man told her that they had passed by a few days before. The he added : 'They have turned to stone along the way. You, too, will turn to stone unless you follow my advice. I have lived here hundreds of years, and have never seen a single person climb to the top of this mountain. If you want to find your brothers, stop up your ears with cotton, and no matter what you hear, don't turn to look back.'

María thanked the old man, ate her lunch, and did as he told her. »

L'homme, vivant dans une cabane, est ici secourable, il prodigue de bons conseils à la jeune fille, pour la suite de sa quête.

Le même conte (donc du type AT 707) a été collecté en Gaspésie, où le dialogue se tient ainsi :

« Bonjour, belle étrangère, lui répondit [le vieillard].

- Mon bon vieillard, vous me semblez malheureux. Vos sourcils sont si longs que vous ne paraissez pas voir clair. Si vous le vouliez, je les couperais. Je raccourcirais aussi votre barbe et vos cheveux. »

Derniers cas en Amérique du Sud

Enfin, en Amérique du Sud, chez les Warrau, on dit des esprits du bush qu'ils sont poilus, et qu'ils ont des sourcils si gros qu'ils ne peuvent regarder en haut qu'en s'allongeant sur le dos. Ce sont en général des créatures maléfiques. Chez leurs voisins Arawaks du Venezuela, un héros décepteur, « Fait-d'Os » se rend chez son grand-père Dáinali afin d'obtenir pour son peuple la nuit et le sommeil. Mais le grand-père en question se plaint d'avoir des paupières trop longues, qui lui tombent devant les yeux et l'empêche de voir s'il ne les soulève pas à la main. Le héros, après une nuit sans sommeil et une discussion avec son grand-père, obtient le moyen d'obtenir le sommeil : des morceaux du talon de Dáinali.

Dans le Pacifique

On retrouve des esprits de ce genre, nommés Menehunes, à Hawaï, où ils sont des lutins censés avoir la peau rouge, et des gros yeux cachés par de longs sourcils. Ils ne sont en général pas hostiles.

En Micronésie, les Ifaluk racontent qu'un jour le dieu Lugweilang discuta avec son père, le démiurge :

« Lugweilang told the wishes of his father [Aluelap, le démiurge] to the people. They all cut a coconut tree, and opened his eyes by raising his eyelids with the tree. But still he could not see, for there were many foreign objects in his eyes. »

Il faudra l'intervention d'un des membres de l'assemblée pour nettoyer les yeux du dieu, qui peut alors constater que tout va bien.

IIe partie

Quelques pistes d'analyse

Quels types de récit ?

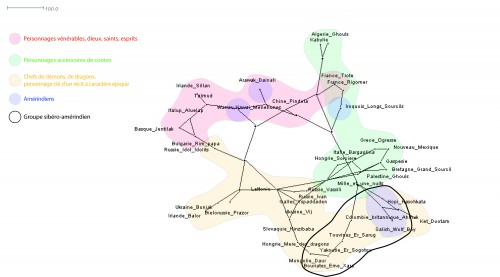

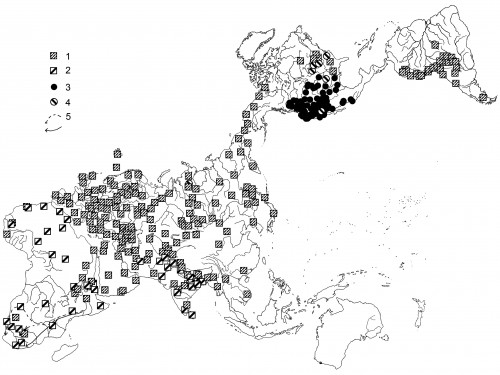

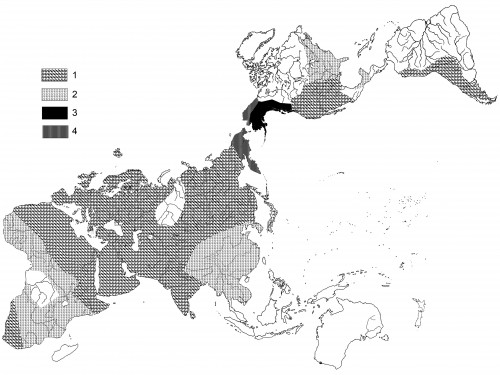

Il est clair, après avoir lu l'ensemble des textes ci-dessus, que l'on n'a pas affaire à un mythe en tant que tel, ni même à un conte-type, mais plutôt à un mythème ou à un motif, voire tout simplement à un personnage-type lorsque celui-ci ne s'insère pas dans un récit : en cela, la situation est très similaire à ce qui existe en Russie et chez les Slaves de l'Est concernant la célèbre sorcière Baba Yaga (que l'on voit d'ailleurs apparaître dans les cas signalés ici) : celle-ci est présente dans des contes de types extrêmement divers. Ainsi, nous avons affaire ici à des personnages isolés à caractère légendaire (France, Chine, Colombie Britannique, Iroquois Seneca, Warau, Hawaï), à des légendes à caractère mythologique (Irlande, Ukraine, Biélorussie, Talmud de Babylone, Sibérie méridionale, Salishs, Hopi), aux contes-types AT 300A (Hongrie, Russie, Mongolie, sans doute France), AT 303 (Ukraine), AT 307 (Ukraine, Lettonie), AT 314 (Palestine), AT 327B (Palestine), AT 400 (Russie), AT 408 (Italie), AT 409b (Hongrie), AT 425 (Grèce), AT 513A (Pays de Galles, Russie), AT 560 (Bretagne), AT 590 (Palestine), AT 707 (Égypte et ailleurs, Nouveau-Mexique, Gaspésie).

Il faut donc plus chercher à caractériser le personnage lui-même et le mythème dans lequel il s'insère, une analyse qui sera délicate car le personnage en question peut être de nature très diverse : nous avons ainsi des géants (Irlande, Pays de Galles, Bretagne, Ukraine, Biélorussie, Russie, Touvines), le « roi des lions » (Russie), des démons (Ukraine, Lettonie), des goules, donc des ogres (Algérie, Palestine), des vieillards (Algérie, Colombie britannique, Iroquois Seneca, Hopi, Nouveau-Mexique, Gaspésie) des saints ou personnages vénérables (Irlande, Ukraine, Talmud de Babylone, Égypte, Algérie, Chine), des sorcières de type Baba Yaga (France, Hongrie, Slovaquie, Ket, Daur, Bouriates), une petite femme, donc une fée (Italie), une ogresse (Grèce) ou tout simplement une vieille femme (Salish).

S'il est une évidence, c'est que ce personnage est vieux, et qu'il possède des sourcils ou des paupières particulières : ce dernier détail est très variable et finalement importe peu. On voit ainsi en Grèce une ogresse aux longues paupières, mise dans la même situation que ses homologues, se faire « coiffer » par amputation des dites paupières. Cette extrême longueur des sourcils (et accessoirement des paupières) est considérée depuis l'Antiquité comme une marque de vieillesse. Ainsi, Aristote écrivait :

« Les poils autres que ceux-là poussent proportionnellement plus ou moins longs ; ce sont surtout ceux de la tête qui poussent le plus; puis, ceux de la barbe ; les plus fins poussent davantage. Chez quelques sujets, les sourcils deviennent si épais dans la vieillesse qu'il faut les couper. »

De fait, un très grand nombre de nos personnages sont qualifiés de vieux. Mais cela ne suffit pas, car on voit ainsi des vieilles aux très longs sourcils apparaître dans certaines versions du conte-type AT 501 « les trois fileuses », sans qu'il n'y ait de lien précis avec les personnages qui nous occupent. Ce critère ne suffit donc pas : il faut aussi qu'un moyen artificiel de soulever ces sourcils ou ces paupières soit mis en œuvre. Ce moyen apparaît cependant aussi dans des contes sans lien avec notre corpus, par exemple dans un conte roumain où l'on veut juste souligner l'extrême vieillesse du héros, ou dans un conte hindou recueilli dans la vallée de Kangra, au pied de l'Himalaya :

« At that time, people lived lives that spanned hundreds and hundreds of years. They couldn't see well as they walked around. This was because they had become so wrinkled that their eyelids had folded over their eyes. To see anything, they had to lift up an eyelid […] and when they'd done whatever they needed to do, they'd let the lid flop down again. »

Là encore, il s'agit uniquement de souligner l'extrême vieillesse des protagonistes et rien d'autre.

Le rôle de la vision

La plupart de nos personnages appartiennent clairement à l'autre-monde. C'est évidemment de part leur nature (géants, ogres, sorciers, etc.). Cela l'est aussi par leur localisation : beaucoup vivent dans des endroits isolés, en pleine forêt, dans des cabanes (en France, en Bretagne, en Hongrie, en Slovaquie, chez les Ket, les Iroquois, les Hopi, au Nouveau-Mexique, en Gaspésie). Une (en Italie), se tient près d'un pont. D'autres sont souterrains (en Russie, chez les Salish, en Algérie). Mais le signe le plus concret de cette appartenance à l'autre-monde est leur incapacité à visualiser, sans aide extérieure, notre monde.

Ce concept de visible / non-visible a largement été exploré par Viatcheslav Ivanov, partant justement de certains personnages de notre corpus et de concepts développés par ailleurs par Vladimir Propp sur l' « invisibilité réciproque ». La relation entre le monde des morts et celui des vivants dépendrait de leur mutuelle invisibilité. C'est pour cela que les dieux des morts sont, ou possèdent des attributs qui rendent invisible, ou bien qui les empêchent de voir le monde des vivants. Cet auteur cite à juste titre Balor et son corrélat gallois Yspaddaden Penkawr : tous deux, maîtres de l'Autre Monde, ont besoin qu'on ouvre artificiellement leur œil pour voir (et tuer ou tenter de tuer) les vivants. Il faut cependant exclure de l'ensemble proposé par Ivanov certains personnages qui, au contraire, n'y voient que trop bien. Ainsi, la Gorgone Méduse, dite blosurôpis « au regard terrifiant » ou « au regard de milan » pour reprendre l'hypothèse d'Ivanov : il n'est nul besoin de lui ouvrir les yeux : bien au contraire, pour pouvoir affronter ce monstre, Persée doit se rendre invisible. Il en est de même pour Argos, panoptès : « qui voit tout ». Afin de pouvoir le tuer, Hermès doit d'abord l'endormir, et donc non pas ouvrir, mais fermer ses paupières. Quelques autres personnages du même type peuvent être joints à cet ensemble. Tout d'abord un géant nommé Vision Acérée, présent dans un conte bohémien collecté par Erben et publié en anglais par Wratislaw. C'est par ce conte que le rapport entre le domaine slave et le domaine celtique a été pour la première fois établi en Occident. « Vision Acérée » doit se bander les yeux car sa vue est si puissante qu'il peut voir normalement à travers le bandeau. Mais s'il l'enlève, il brûle tout ce qu'il regarde. Cependant, le personnage en question n'a aucun problème de paupières, de cils ou de sourcils, il n'est pas un vieillard, et enfin il est particulièrement secourable pour le héros du conte, ce qui tranche complètement avec les autres personnages analysés ici. Autre personnage qui se masque volontairement la vue pour ne pas indisposer ceux qui l'approchent : le légendaire roi danois Olo. La description qui est faite de ce roi dans les Gesta Danorum de Saxo Grammaticus est édifiante :

« […] Olo devint célèbre tant il apparaissait incroyablement doué de qualité physiques et morales, à cela près cependant qu'il avait un air si farouche qu'il obtenait devant l'ennemi le même résultat avec ses yeux que d'autres avec leurs armes, et que même les plus braves d'entre les braves étaient terrifiés par le feu de son regard perçant. »

Cette première description ferait penser à un Cuchulainn ou un Horatius Coclès nordique si elle n'était suivie de deux autres plus extraordinaires, dont une liée à son assassinat par Starkađr :

« Quand il le surprit, tout occupé à se laver, il fut aussitôt subjugué par son regard perçant. Il fut pétrifié par l'éclat fulgurant de ses yeux, d'où sortaient des éclairs, et il sentit ses membres paralysés par une secrète frayeur. Il n'avança point, mais recula plutôt, le pied léger, la main en suspens, incapable d'exécuter son projet. Ainsi, le guerrier qui avait terrassé tant et tant de généraux et de champions ne put supporter le regard d'un homme seul et sans arme.

Olo, tout à fait conscient de l'effet causé par ses prunelles, se couvrit le visage et invita Starcatherus à s'approcher de lui pour qu'il lui transmît le message dont il était porteur. Comme il connaissait l'homme depuis longtemps et qu'une vieille amitié le liait à lui, il était bien loin de songer que quelque piège pût le menacer. Mal lui en prit, car Starcatherus bondit sur lui. Brandissant son épée, celui-ci le poignarda. Puis, comme Olo tentait de se redresser, il le frappa à la gorge. »

Toujours dans le registre des rois au regard maléfique, l'Arménien Eouant peut paraître assez proche de l'Irlandais Sillan et du Kas'jan russo-ukrainien :

« On raconte qu’Erouant, selon la magie, avait le mauvais œil; c’est pourquoi, chaque matin, les chambellans du palais avaient l’habitude de placer des pierres très dures en face d’Erouant, et qu’elles se fendaient [sous l’influence] de la malignité de son regard. Mais, ou ceci est faux ou fabuleux, ou bien cela veut dire qu’il avait la puissance diabolique de nuire, et l’influence du mauvais œil, à tous ceux auxquels il en voulait. »

Cependant, il se place dans la même catégorie qu'Olo : il n'a nul besoin d'aide pour ouvrir ses yeux (alors que même Sillan finit par être « coiffé »).

Le fait d'avoir un regard maléfique est loin d'être systématique chez nos personnages (le fait n'apparaît réellement qu'en Irlande, en Ukraine, et chez les Salish), et surtout, aucun ne ferme ou ne fait fermer volontairement ses yeux. Balor voit bien son œil crevé, mais c'est uniquement après l'avoir ouvert et avoir vu son adversaire, qui ne se cache d'ailleurs pas.

Quelle structure pour quel mythème ?

Pour que le mythème soit finalement bien identifié, il faut au moins les éléments suivants :

- un héros, jeune, en quête. Il peut s'agir d'une femme (conte-type AT 707, par exemple), mais c'est le plus souvent un homme ;

- dans le cadre de sa quête il découvre une créature aux sourcils ou aux paupières très longs ;

- la créature exprime alors le souhait de voir son interlocuteur ;

- des serviteurs soulèvent les paupières ou les sourcils de la créature, ou bien le héros le fait lui-même ;

- la créature peut alors être, selon les contes dans lesquels le mythème s'insère, hostile ou bénéfique. S'il y a hostilité, dans une légende à caractère mythologique, il y a combat ; dans un conte il y a imposition d'épreuves insurmontables. Autrement la créature indique au héros le chemin à prendre pour la suite de sa quête.

Le vœu exprimé par la créature de voir son interlocuteur est relativement constant d'une version à l'autre. C'est sur celui-ci que j'avais concentré mon étude de 2012, centré sur les Celtes et les Slaves. Je me permettrai de la reprendre ici :

Nous avons donc quatre phrases:

-

en gallois: Drycheuwch y fyrch y dan uyn deu amrant hyt pan welwyf defnyt uyn daw.

-

en irlandais: Tócaib mo malaig, a gille,' al Balor, 'co ndoécius an fer rescach fil ocom acallaim.

-

en russe: Voz'mite-ka vily železnyja, podymite moi brovi i resnicy čornyja, ja pogljažu, čto on za ptica, čto ubil moix synovej.

-

en biélorusse: Slugi mae vernyja, padymicja mne vilkami brovy! Xaceu en pagljadzec' na Illjušku.

L'ensemble de ces données replacées dans un tableau est éclairant:

|

Texte gallois

|

Mac uy gweisson drwc a'm direidyeit? Heb ynteu

|

Drycheuwch y fyrch

|

y dan uyn amrant

|

hyt pan welwyf

|

defnyt uyn daw

|

|

traduction

|

Où sont mes serviteurs, ces manants, ces gens de rien?

|

Levez les fourches

|

sous mes deux paupières

|

que je puisse voir

|

la future apparence de mon gendre

|

|

Commentaires lexicaux

|

Gweisson: pl. de gwas = irl. fors (valet), = français valet

|

Drychafael: « lever » < *to-ro-uss-kab-

fyrch: pl. de forch

|

Amrant: « paupière »

|

Gwelet: « voir »

< *wel-

|

|

|

Texte irlandais

|

A gille,

|

Tócaib

|

mo malaig

|

'co ndoécius

|

an fer rescach fil ocom acallaim

|

|

traduction

|

Mes « garçons » = serviteurs

|

Levez

|

mes paupières

|

que je puisse voir

|

le bavard qui discute avec moi

|

|

Commentaires lexicaux

|

Giolla: cf. anglo-saxon cild: « enfant ». < *gel-1: « entourer, encercler »

|

Do-furgaib: « il lève » < *to-ro-uss-gab-

|

Malaig: « paupière »

|

Do-écai: « voir »

|

|

|

Texte biélorusse

|

Slugi mae vernyja

|

padymicja mne vilkami

|

brovy!

|

Xaceu en pagljadzec'

|

na Illjušku

|

|

traduction

|

Mes serviteurs fidèles

|

soulevez avec les fourches

|

mes sourcils!

|

Il voulait voir

|

Illjuška

|

|

Commentaires lexicaux

|

Slugi: « serviteurs », cf. gaul. slougo, irl. Slúag: « troupe ».

|

Dymac: « lever »

vilkami: littéralement « petites fourches »

|

Brovy: « sourcils »

|

gljadzec': « regarder, voir »

cf. irl. glé; gaul. gliso-

|

|

|

Texte russe

|

|

Vozmite-ka vily železnyja, podymite

|

Moi brovi i resnicy čornyja.

|

Ja pogljažu

|

čto on za ptica čto ubil moix synovej

|

|

traduction

|

|

Prenez les fourches de fer, soulevez

|

Mes sourcils et mes cils noirs (épais).

|

Je jetterai un coup d'oeil (regarderai)

|

Quel est cet oiseau qui a tué mes fils

|

|

Restitution générale

|

Mes serviteurs,

|

levez avec les fourches

|

mes sourcils / paupières.

|

Je veux voir

|

.....

|

Les différences lexicales entre ces versions montrent bien qu'on a ici non pas des traductions, mais une seule et même phrase héritée. Chez les Slaves, il est question de « sourcils », chez les Celtes de « paupières ». Dans tous les cas, on emploie un mot ayant le sens de « serviteur », mais dans tous les cas aussi, ce mot a vraisemblablement eu un autre sens. Le biélorusse et russe slugi est bien apparenté au gaulois slougo: « troupe (armée) ». L'irlandais giolla désignait assez vraisemblablement « ceux qui entourent », alors que le gallois gwas vient du gaulois vasso-, lequel a donné en français « vassal ». Les serviteurs de la version russe sont clairement désignés par le terme bogatyr : « vaillant, preux ». Le sens de serviteur est donc toujours secondaire: primitivement, il est possible que nous ayons ici une forme de Männerbund entourant le chef des démons. Enfin, on notera que dans tous les cas (sauf le biélorusse), l'objet de l'action, la personne que le géant veut voir, est désigné par un sarcasme: « futur gendre » en gallois (sous entendu « celui qui ne parviendra jamais à le devenir »), « bavard » en irlandais, « oiseau » en russe.

Ces formules se retrouvent de façon plus ou moins proche dans d'autres textes de notre corpus :

« My dear girls, just prop up my two eyes with that iron bar, which weighs twelve hundred pounds, so that I may look around. » (Hongrie)

« But there is a pitchfork in the corner. Sitck it into my eyelashes so that I should see you ! » (Hongrie)

« Soulevez mes paupières, je ne vois pas ! » (Ukraine = Gogol)

« Hola, mes sept enfants! Prenez les fourches de fer pour me soulever les paupières, afin que je puisse regarder ce vaillant gaillard! » (Russie)

« Apportez ces sept fourches, soulevez mes sourcils : je veux les voir. » (Russie)

« Mes fils, prenez une fourche et soulevez mes sourcils. Alors, je le verrai quand même ! » (Lettonie)

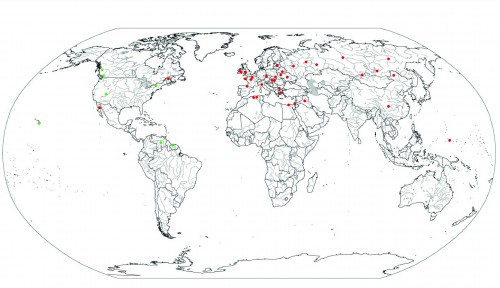

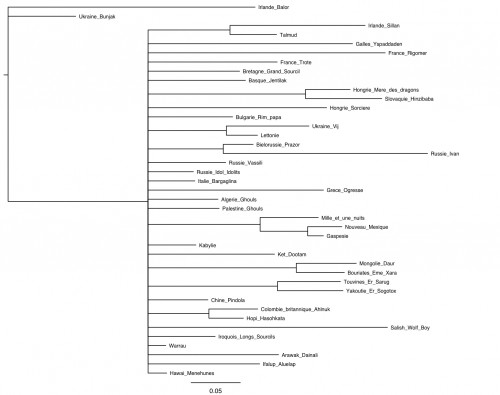

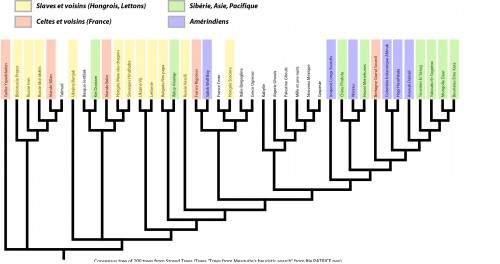

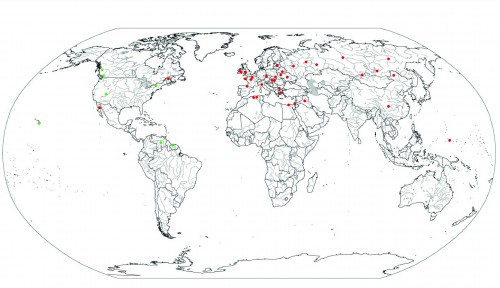

« Lift my eyelids a little, so I can see you » (Italie)